Issue XXIV December 2016

Poetry from Ireland

edited by Patrick Cotter

Every litterateur shouldn’t be concerned just about reading and writing for oneself. There must be few among the lot to endeavour towards making materials available for reading. There must be few who find it useful to devote time behind building avenues for writers apart from reading and writing for themselves. History washes off the contribution of editors leaving the useful residue in the form of novels, short stories, poems, dramas or any other narrative of literature but still editing and publishing has to be done to allow literature to flourish. The people behind The Enchanting Verses Literary Review have been moving with this realism in mind and the good thing is that they never complain while creating avenues for writers and readers. They have divided their hours judiciously to act both as writers and editors. I cannot thank Patrick Cotter enough for knitting this marvellous issue together.

Until this edition, I had never ventured much into Irish poetry except W.B. Yeats. The reason is obvious— Yeats’s connection to Tagore and Tagore’s influence over Indians. Yeats in his introduction to Tagore’s book Gitanjali said, “We write long books where no page perhaps has any quality to make writing a pleasure, being confident in some general design, just as we fight and make money and fill our heads with politics---all dull things in the doing---while Mr. Tagore, like the Indian civilization itself, has been content to discover the soul and surrender himself to its spontaneity.” I still doubt Yeats’s understanding of Tagore’s poetry but the aesthetics of emotional sensitivities was congruous with Tagore’s muses. Similarly, I believe the understanding of any anglophone Asian about this anthology will rest within the emotional whereabouts of the poets presented through their poems in this anthology. I consider poetry cannot be spontaneous but thoughts can be. Writing always takes time and poetry is no exception. Moreover, it is much similar to painting. Painting is drawing lines in a particular fashion to create something intriguing or something that soothes our eyes. Poetry is using words instead of those lines and arranging them in a distinct fashion to create something that presents the poet’s perspective in N no of ways. Each poet in this anthology presents a distinct style of shaping their thoughts into words.

Coming to the language, English cannot be termed as a language with a firm linguistic quality. Dialects differ from country to country where English is spoken by a considerable majority. There are roots hidden beneath various dialects and they have been the cause of various types of English that are written and spoken today. For example, Indian English has to be the outcome of prevailing Indian dialects and the British colonisation in India. Similarly, the English in many of the poems in the anthology seems to present a dialect of their own as compared to American, British, Australian or Indian English. Though English is the main language of Ireland, the effect of vernaculars and the local linguistic slant cannot be denied. I had a feeling while reading this edition that Irish poets prefer to be extremely personal at times and sometimes it is almost impossible to get to the theme without knowing the background of a particular poem. But, the fascinating thing is these poems are all well dressed and pruned and they allow us to muse and question ourselves towards the end. Every genuine poetry lover looks out for interpretations rather than landing upon concrete conclusions while reading a poem. The Irish poets seem to provide enough room for these interpretations. Starting from John Montague’s Star Song to Thomas McCarthy’s Windswept the issue is a panorama of expressions, fresh turns of phrase and viewpoints that would help us understand what Poetry is to Ireland and what Ireland is to the world of Poetry.

Sonnet Mondal

Editor in Chief

The Enchanting Verses Literary Review

Until this edition, I had never ventured much into Irish poetry except W.B. Yeats. The reason is obvious— Yeats’s connection to Tagore and Tagore’s influence over Indians. Yeats in his introduction to Tagore’s book Gitanjali said, “We write long books where no page perhaps has any quality to make writing a pleasure, being confident in some general design, just as we fight and make money and fill our heads with politics---all dull things in the doing---while Mr. Tagore, like the Indian civilization itself, has been content to discover the soul and surrender himself to its spontaneity.” I still doubt Yeats’s understanding of Tagore’s poetry but the aesthetics of emotional sensitivities was congruous with Tagore’s muses. Similarly, I believe the understanding of any anglophone Asian about this anthology will rest within the emotional whereabouts of the poets presented through their poems in this anthology. I consider poetry cannot be spontaneous but thoughts can be. Writing always takes time and poetry is no exception. Moreover, it is much similar to painting. Painting is drawing lines in a particular fashion to create something intriguing or something that soothes our eyes. Poetry is using words instead of those lines and arranging them in a distinct fashion to create something that presents the poet’s perspective in N no of ways. Each poet in this anthology presents a distinct style of shaping their thoughts into words.

Coming to the language, English cannot be termed as a language with a firm linguistic quality. Dialects differ from country to country where English is spoken by a considerable majority. There are roots hidden beneath various dialects and they have been the cause of various types of English that are written and spoken today. For example, Indian English has to be the outcome of prevailing Indian dialects and the British colonisation in India. Similarly, the English in many of the poems in the anthology seems to present a dialect of their own as compared to American, British, Australian or Indian English. Though English is the main language of Ireland, the effect of vernaculars and the local linguistic slant cannot be denied. I had a feeling while reading this edition that Irish poets prefer to be extremely personal at times and sometimes it is almost impossible to get to the theme without knowing the background of a particular poem. But, the fascinating thing is these poems are all well dressed and pruned and they allow us to muse and question ourselves towards the end. Every genuine poetry lover looks out for interpretations rather than landing upon concrete conclusions while reading a poem. The Irish poets seem to provide enough room for these interpretations. Starting from John Montague’s Star Song to Thomas McCarthy’s Windswept the issue is a panorama of expressions, fresh turns of phrase and viewpoints that would help us understand what Poetry is to Ireland and what Ireland is to the world of Poetry.

Sonnet Mondal

Editor in Chief

The Enchanting Verses Literary Review

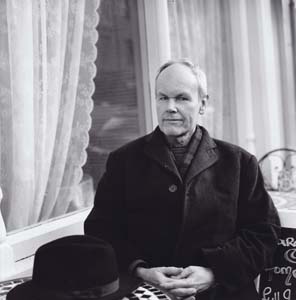

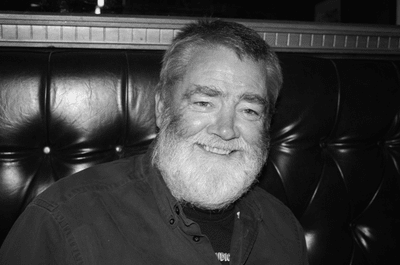

John Montague - Enchanting Poet John Montague John Montague

John Montague (1929-2016) was one of the best known Irish contemporary poets. He was born in New York and brought up in Tyrone. He has published a number of volumes of poetry, two collections of short stories and two volumes of memoir. In 1998 he became the first occupant of the Ireland Chair of Poetry. In 2010, he was honoured with Chevalier de la Legion d’honneur, France’s highest civil award.

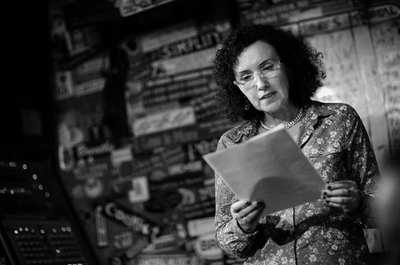

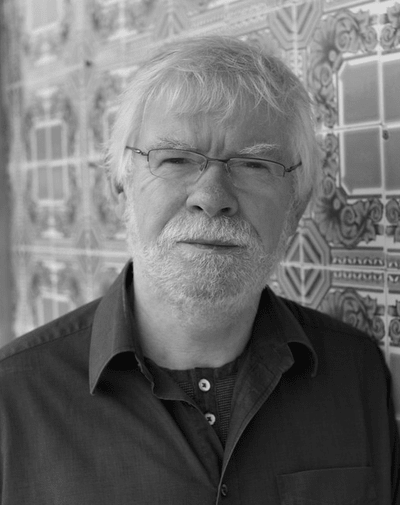

Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin- Editor's Choice Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin

Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin was educated at University College Cork and The University of Oxford. She is a Fellow of Trinity College Dublin and an emeritus professor of the School of English which she joined in 1966. Ní Chuilleanáin is a founder of the literary magazine Cyphers. Her first collection won the Patrick Kavanagh Poetry Award in 1973. In 2010 The Sun-fish was the winner of the Canadian-based International Griffin Poetry Prize and was shortlisted for the Poetry Now Award. In 2016 she was appointed Ireland Professor of Poetry by the President of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins.

|

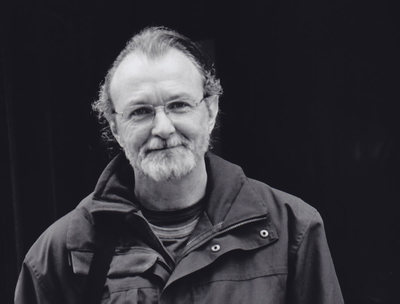

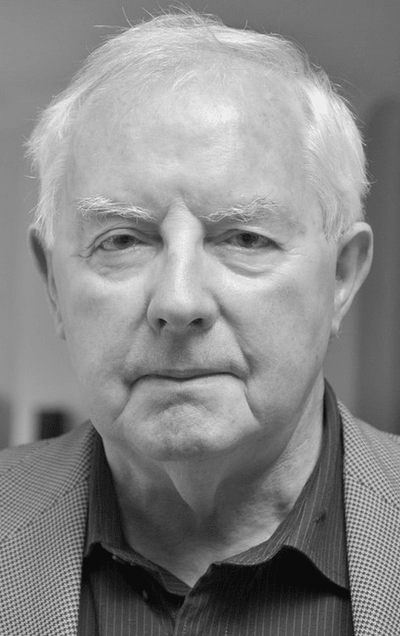

from Patrick Cotter, Guest Editor Issue XXIV Patrick Cotter Patrick Cotter

English has been the language with which Irish poets have built international reputations, the achievements of W.B. Yeats and Seamus Heaney mirror that of Rabindranath Tagore. But just as India has fabulous poets in Hindi, Malayalam, Tamil and in hundreds of other tongues, Ireland has marvellous poets working in the Irish language and in this miscellany of Irish poets you will find some. Most Anglophone Indians also speak another language. Most Anglophone Irish do not. Ireland shared a colonial master with India. Ireland endured occupation a few centuries longer which meant that the island’s native language suffered attrition and while remaining culturally significant is spoken by only a minority today.

The Irish writing in English have distinguished themselves with a variety of English which is askew from standard English, conveying a different music and different way of looking at the world, shaped by the grammar and logic of the Irish language. Narrative – derived from the ancient literature in the Irish language predominates our poetry, but explorations of family and history are prevalent too. Since the 1990s Irish women have been published in increasing numbers and asserting themselves as accomplished poets. There is an old joke about there being a standing army of Irish poets but there are at least two hundred currently in print with books to call their own. It is impossible to represent them all. In 2015 I guest-edited an Irish issue of Poetry and presented a selection of poets under forty. Most of the poets here are over fifty years of age. Anyone who would like to seek out other Irish poets not represented here could begin by checking out the following websites: http://www.poetryinternationalweb.net/pi/site/country/item/30/Ireland https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/toc/detail/71530 http://www.munsterlit.ie/Southword/issues_index.html7 |

All Poets & Poems

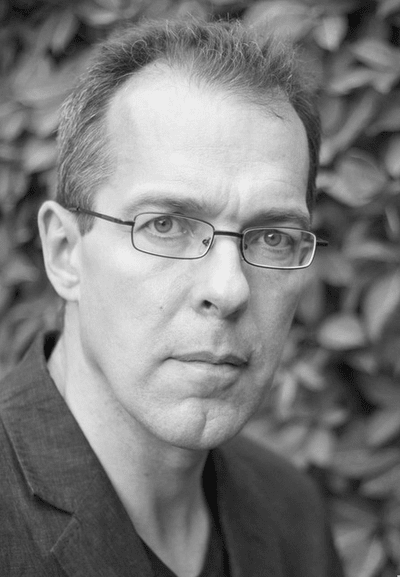

Social Realism Thwarted

by Patrick Cotter

The Boys of Bluehill Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, The Gallery Press, 2015, €11.95pbk €18.50hbk; Wake Forest University Press $13.95pbk

There Now Eamon Grennan, The Gallery Press, 2015, €11.95pbk €18.50hbk; Graywolf Press in the USA

by Patrick Cotter

The Boys of Bluehill Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, The Gallery Press, 2015, €11.95pbk €18.50hbk; Wake Forest University Press $13.95pbk

There Now Eamon Grennan, The Gallery Press, 2015, €11.95pbk €18.50hbk; Graywolf Press in the USA