FROM "VIOLA ARSENICA: NOTES ON POETRY"

ARS POETICA

by Vlada Uroshevikj

My ideal, regarding poetry, is to create a poem impossible to interpret: solid, encapsulated, impenetrable, and sufficient on its own - like a round pebble that has been smoothened out and left on shore by the sea. I am not saying that I have succeeded in writing this kind of poem, nor am I certain that I ever will. In my view, the poem should contain some sort of regularity within itself. That is why I sometimes write rhymed poetry. All words in the poem should somehow spontaneously come to mind one by one - it is as if the language in which the poem is written envisages this, and as if this could not be said in any other way. What should the poem express? In poetry, I try to restrain myself as much as possible from uttering “wise quotes” like sententiae, definitions, and very explicitly expressed ideas. Very often I find myself repeating that famous introduction from Tao Te Ching: “The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao”.

Nothing terrifies me more than saying something that has been said many times before.

I renounce the generally accepted truths in advance. That is why even a small tremor of something that is hinted at and which will likely remain a mystery is more significant for poetry rather than a loud, thunderous shout of viewpoints that anyone could have.

A nuance, even if not expressed clearly enough but hints toward a new approach to the ultimate goal is more precious to me than a standpoint that is skillfully conveyed, but too easily attainable.

The best salvation from banality is leaning toward the surprise and the unanticipated.

If the point of poetry was to convey clearly defined and undeniable statements then there is no need for verses: for that purpose prose, be it moral or philosophical, would suffice.

Too much rationality impairs poetry. For a poem to attain and remain in the form of poetry it requires a certain amount of foolhardiness achieved through play, leaning toward coincidences, associative connections, humor, or some kind of verbal trance - in order to reach an area in which rationality cannot penetrate.

Ordinary speech is designed to convey messages that are understandable to anyone. The poetic language is an attempt to use those messages in order to scratch the surface of the realm of that which cannot be said.

I consider the information obtained through sensory stimuli to be of vital importance: it is sort of a pass for entering through the gates of enigmatic sense that leads to the peak of transcendence. Therefore, the senses’ ability to respond to extremely subtle stimuli is a sign that signals the readiness to discover a particular poetic sense in all things

The strengthening of the religious feeling does not lead to discoveries of the poetic kind: the field of religion is completely filled with a different kind of sense in which there is no place for individual poetic content. Moments of an emphasized feeling of the senses are very often a kind of reminder of that same emphasized receptivity of the manifestations of nature we have had during childhood; the poetic search for that sensory sharpness is always seen as a search for the child in oneself. Poetry is the discovery of the hidden links between things that, through the links thus revealed, show their essence, but also the essence of the world.

The poet deciphers the essence of things, but in order to convey it he needs to encrypt it again in a different way.

Poetry is an act of enchantment: just like the sorcerers from the past, the poet also casts spells, making the world do his bidding, or in other words reveal its marvelousness.

(Published as a supplement to the book: ”The Seventh Side of the Cube”, 2010)

THE PURPOSE OF POETRY

Quite a few years ago, in a conversation I had with the students of a high school in Skopje to which I was invited, a boy posed the question: Why should someone in today’s age write poetry, when nearly no one reads it? And what practical use can we have from reading poetry? The question was open, direct, and relentless. I do not remember what my answer was at that moment, but the question lingered in my mind later on while trying to find my own possible answers.

Undoubtedly, the boy was partially right: poetry is not read nearly enough today, and its impact on the world cannot be felt. The circulations of collected poems are drastically decreasing. Poetry is standing on the margins of social life. The questions that this high school student posed are not discussed publicly, I would say out of decency, but every poet feels their weight on their shoulders.

Of course, there have been eras in the past when poetry played a much more significant role in forming young people’s sensibilities, when it was a great source of information, and when what the poet said had a much greater resonance. However, today the poet is no longer a sorcerer, a prophet, or a great leader. Perhaps Léopold Sédar Senghor was the last poet to be chosen as a president of a country; in the present and probably in the future that position will be occupied by people from some other more prosaic professions. Today, the poet is no longer the one who speaks in the name of the people, before a large audience, he does not claim to possess a gift given to him by God. But he also doesn’t submit to being a court jester, a showman, or a circus performer who provides light entertainment for the people who seek it. He complies with being someone with no privileges, no honors, whose voice cannot be heard in a larger area - he withdraws from the front rows of public stages; in order to preserve his individuality and his dignity, he accepts being a humble citizen - a citizen, it is true, with a rather unorthodox profession, with his own personal goals and his own language, but also with a right to his own morality and freedom.

What is the purpose of his writing of poetry? Why does the poetry that he creates need to live on?

We could probably answer this with some pathetic phrase about how without poetry the world would have no soul, no meaning, no depth, and so on. But these are just pretty words that few people believe. Let us be honest, the world, unfortunately, would be able to carry on without poetry and only a few people would feel the emptiness from its disappearance.

So, why then continue to write poetry?

My answer is: out of beautiful stubbornness. Out of the desire to have at least one occupation in this so mercantile, so technological, so deprived of spirituality, and so cruelly pragmatic world that does not, in any case, bring either power or great fame or money. Poetry needs to exist for an ineffable purpose, which does not coincide with any practical and useful value, just as without any visible and reasonably accessible purpose, this planet revolves in the middle of the incomprehensible universe.

(Read at the National and University Library - “St. Clement of Ohrid“ in Skopje on the occasion of Poetry day, April 21, 2012)

Translated from Macedonian by Viktor Velkovski

Proofread by Kalina Maleska

These texts are excerpts from the book “Viola Arsenica: Notes on Poetry” (2021), in which academician Vlada Uroshevikj expresses his views on poetry and poetic art. The book consists of excerpts from his essays, discussions, interviews, speeches, autobiographical texts, and afterwords. It offers a fragmentary and concise overview of what poetry means to the author; its preoccupations, goals, essential characteristics, and its future in a time that is increasingly marginalizing it.

These are the first translations into English of parts of this book written by Vlada Uroshevikj and their first publication is in this issue of Verseville magazine, dedicated to contemporary Macedonian poetry.

Nothing terrifies me more than saying something that has been said many times before.

I renounce the generally accepted truths in advance. That is why even a small tremor of something that is hinted at and which will likely remain a mystery is more significant for poetry rather than a loud, thunderous shout of viewpoints that anyone could have.

A nuance, even if not expressed clearly enough but hints toward a new approach to the ultimate goal is more precious to me than a standpoint that is skillfully conveyed, but too easily attainable.

The best salvation from banality is leaning toward the surprise and the unanticipated.

If the point of poetry was to convey clearly defined and undeniable statements then there is no need for verses: for that purpose prose, be it moral or philosophical, would suffice.

Too much rationality impairs poetry. For a poem to attain and remain in the form of poetry it requires a certain amount of foolhardiness achieved through play, leaning toward coincidences, associative connections, humor, or some kind of verbal trance - in order to reach an area in which rationality cannot penetrate.

Ordinary speech is designed to convey messages that are understandable to anyone. The poetic language is an attempt to use those messages in order to scratch the surface of the realm of that which cannot be said.

I consider the information obtained through sensory stimuli to be of vital importance: it is sort of a pass for entering through the gates of enigmatic sense that leads to the peak of transcendence. Therefore, the senses’ ability to respond to extremely subtle stimuli is a sign that signals the readiness to discover a particular poetic sense in all things

The strengthening of the religious feeling does not lead to discoveries of the poetic kind: the field of religion is completely filled with a different kind of sense in which there is no place for individual poetic content. Moments of an emphasized feeling of the senses are very often a kind of reminder of that same emphasized receptivity of the manifestations of nature we have had during childhood; the poetic search for that sensory sharpness is always seen as a search for the child in oneself. Poetry is the discovery of the hidden links between things that, through the links thus revealed, show their essence, but also the essence of the world.

The poet deciphers the essence of things, but in order to convey it he needs to encrypt it again in a different way.

Poetry is an act of enchantment: just like the sorcerers from the past, the poet also casts spells, making the world do his bidding, or in other words reveal its marvelousness.

(Published as a supplement to the book: ”The Seventh Side of the Cube”, 2010)

THE PURPOSE OF POETRY

Quite a few years ago, in a conversation I had with the students of a high school in Skopje to which I was invited, a boy posed the question: Why should someone in today’s age write poetry, when nearly no one reads it? And what practical use can we have from reading poetry? The question was open, direct, and relentless. I do not remember what my answer was at that moment, but the question lingered in my mind later on while trying to find my own possible answers.

Undoubtedly, the boy was partially right: poetry is not read nearly enough today, and its impact on the world cannot be felt. The circulations of collected poems are drastically decreasing. Poetry is standing on the margins of social life. The questions that this high school student posed are not discussed publicly, I would say out of decency, but every poet feels their weight on their shoulders.

Of course, there have been eras in the past when poetry played a much more significant role in forming young people’s sensibilities, when it was a great source of information, and when what the poet said had a much greater resonance. However, today the poet is no longer a sorcerer, a prophet, or a great leader. Perhaps Léopold Sédar Senghor was the last poet to be chosen as a president of a country; in the present and probably in the future that position will be occupied by people from some other more prosaic professions. Today, the poet is no longer the one who speaks in the name of the people, before a large audience, he does not claim to possess a gift given to him by God. But he also doesn’t submit to being a court jester, a showman, or a circus performer who provides light entertainment for the people who seek it. He complies with being someone with no privileges, no honors, whose voice cannot be heard in a larger area - he withdraws from the front rows of public stages; in order to preserve his individuality and his dignity, he accepts being a humble citizen - a citizen, it is true, with a rather unorthodox profession, with his own personal goals and his own language, but also with a right to his own morality and freedom.

What is the purpose of his writing of poetry? Why does the poetry that he creates need to live on?

We could probably answer this with some pathetic phrase about how without poetry the world would have no soul, no meaning, no depth, and so on. But these are just pretty words that few people believe. Let us be honest, the world, unfortunately, would be able to carry on without poetry and only a few people would feel the emptiness from its disappearance.

So, why then continue to write poetry?

My answer is: out of beautiful stubbornness. Out of the desire to have at least one occupation in this so mercantile, so technological, so deprived of spirituality, and so cruelly pragmatic world that does not, in any case, bring either power or great fame or money. Poetry needs to exist for an ineffable purpose, which does not coincide with any practical and useful value, just as without any visible and reasonably accessible purpose, this planet revolves in the middle of the incomprehensible universe.

(Read at the National and University Library - “St. Clement of Ohrid“ in Skopje on the occasion of Poetry day, April 21, 2012)

Translated from Macedonian by Viktor Velkovski

Proofread by Kalina Maleska

These texts are excerpts from the book “Viola Arsenica: Notes on Poetry” (2021), in which academician Vlada Uroshevikj expresses his views on poetry and poetic art. The book consists of excerpts from his essays, discussions, interviews, speeches, autobiographical texts, and afterwords. It offers a fragmentary and concise overview of what poetry means to the author; its preoccupations, goals, essential characteristics, and its future in a time that is increasingly marginalizing it.

These are the first translations into English of parts of this book written by Vlada Uroshevikj and their first publication is in this issue of Verseville magazine, dedicated to contemporary Macedonian poetry.

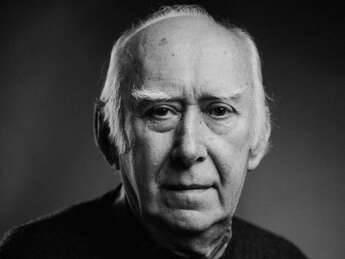

Vlada Uroshevikj (1934) – poet, short story writer, novelist, literature and art critic, essay writer, translator, winner of the Golden Wreath Award at the Struga Poetry Evenings Festival 2023 – one of the most important international poetry awards in the world. With over fifty published books as an author and editor, he previously worked as a professor at the Department of General and Comparative Literature, Blazhe Koneski Faculty of Philology, Ss. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje. His poetry has been translated into numerous languages and he has compiled several anthologies of Macedonian and French poetry and short stories. Additionally he has translated over 30 titles from Macedonian and over 20 from the other languages of the former Yugoslavia and from French into Macedonian. Recipient of the most important awards for poetry and prose in Macedonia, including the Novel of the Year Award in 2022, as well as international literary awards. Winner of the state award for life's workfor achievements in culture and art. Corresponding member of the international Academie Mallarme in Paris and a regular member of the European Literary Academy in Luxembourg. Full member of the Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts and a member of the European Academy of Sciences and Arts. Vlada Uroshevikj is also a member of MASA, of the Macedonian PEN Centre and the Macedonian Writers’ Association.