Deep Fish—Three Passes at Larry Levis’ Immortal Poem by Suzanne Lummis

|

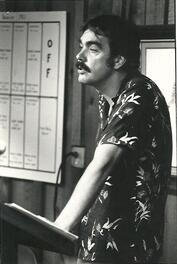

Larry Levis giving a lecture, at the Aspen Writers' Conference, 1980.

“He was jealous of my Hawaiian shirts, so he went out and bought one of his own.” – Kurt Brown, Facebook post “Larry wasn't awake for this one either. But he could say wise things about poetry in his sleep.” - Ira Sadoff, FB post on Kurt Brown's FB page |

Larry Levis

FISH for Philip Levine The cop holds me up like a fish; he feels the huge bones surrounding my eyes, and he runs a thumb under them, lifting my eyelids as if they were envelopes filled with the night. Now he turns my head back and forth, gently, until I'm so tame and still I could be a tiny, plastic skull left on the dashboard of a junked car. By now he's so sure of me he chews gum, and drops his flashlight to his side; he could be cleaning a trout while the pines rise into the darkness, though tonight trout are freezing into bits of stars under the ice. When he lets me go I feel numb. I feel like a fish burned by his touch, and turn and slip into the cold night rippling with neons, and the razor blades of the poor, and the torn mouths on posters. Once, I thought even through this I could go quietly as a star turning over and over in the deep truce of its light. Now, I must go on repeating the last, filthy words on the lips of this shrunken head, shining out of its death in the moon-- until trout surface with their petrified, round eyes, and the stars begin moving. |

The creation tales and lore of some Native American tribes, some Northwest Coast people certainly, and the Yuchi of the Southeast, posits the existence of three worlds. The Western tradition, in most of its expressions, holds to the idea of two— “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.” Of course, exceptions can be found, especially in poetry.

I like to ask my students, the advanced classes where Larry Levis’ “Fish” is best appreciated—for these poets have probably already attempted what he makes look so very easy—“Where does this poem take place, in the world below, the world above, or this one?”

There is a silence while the group considers the poem from this new point of view then someone will speak up. All three.

Indeed, it moves fluidly, seamlessly, through and around the lower, middle and upper realms, each a chilly landscape glittering with a few sharp details that seem cut with an X-Acto Knife.

“Is it a poem in the high lyric voice or in a natural, speaking voice?” A shorter pause this time, and several respond. Again, both. There’s hardly a word that would stump a fifth grader, not a sentence a sixth grader couldn’t grasp, at least on some level, and the narration rolls forth with seeming spontaneous ease. But “high lyric voice”—oh yes, it’s got that going on. “Once, I thought even through this/I could go quietly as a star turning over and over/in the deep truce of its light….”

Admittedly, the word “truce,” might puzzle some elementary school students, but no more than it will adult readers of poetry. We'll all be puzzled together. And together we'll wonder if the poet might have first written “sluice,” “an act of rinsing or showering with water”— light like a trail of water, yes—then later misread it for “truce.” A ceasefire or cessation of hostilities, he thought (maybe), that’s interesting! In any case, in this mix of images and sounds, both “sluice” and “truce” are sonically gorgeous. I would even have accepted “ruse.”

The poem proceeds in the relaxed, straight-forward manner of a speaking voice yet speaks such things as we have never heard uttered—outside of read-aloud poetry, outside of this poem, on occasions when it’s read aloud. It’s all so simple, and yet the final effect is of mysterious, magisterial gloom.

Sometimes, I invite the group to discover ways in which the images telegraphically connect across many lines, “he feels the huge bones/surrounding my eyes” (and how great a choice is that “huge,” and who among us would’ve thought of it?), with the trout’s “petrified round eyes,” and the “tiny, plastic/skull left on the/dashboard of a junked car” with “the last, filthy/words on the lips/of this shrunken head.” And look how it all fuses at the end, the bone and the stars, the trout pulled from the frozen lake into frozen air, and the gutted “I” (in his present, stunned and anesthetized condition) manhandled by the cop. But this is the head of a man in the hands of a cop, like a decapitated head. That, too, will pass through weird transformations. The “huge” bones shrink in the cop’s hands, become, in the imagination of the speaker, a knickknack discarded along with the junked car. Finally, it occupies the moon, but it’s a desolate head encircled by its own death.

Were that all it’d be plenty, but there’s more, a little move the poem makes half way through, a leap across the urban landscape—the middle world, this one—in a moment of sudden, unwilled seeing (the eye pried open): “the cold/night rippling with neons,/and the razor blades/of the poor,/and the torn mouths on posters.”

Is it dazzling or squalid? Is it earthy or metaphysical? “…pines rise into darkness…trout freeze into bits of stars…the razor blades of the poor…” Both, always both, sinking and rising through those three uneasy landscapes. Dreamscapes.

Among the icy strata only one thing burns, and one thing is branded by that burning.

I can think of another paradox, another opposition, though I’ve never tried this one on my students. Even as the narrator lays bare his humiliation, his utter debasement, the poet ascends into the empyrean. After all, Levis wrote this tour de force, “Fish,” when he was only 25. It announced his arrival, a poet whose name, in certain circles, would eventually take on some of the attributes of lore and legend.

***

In Michele Poulos’ documentary about Larry Levis, A Late Style of Fire, Philip Levine offers this conjecture, “I don’t think he saw it as self-destructiveness. I think he saw it as the pursuit of Duende, if we want to use Lorca’s term, and there was a constant struggle between creation and destruction, and he wanted to be at the center of that, to get what was best for his poetry.”

He's speaking of his student then lifelong friend, the poet whose artistic cachet— mystique—had begun to take hold well before his sudden death. “He was born on one side,” says Levine, “but his soul grew up on the other.”

That “one side” would be the agricultural trade, the orchards and fields of the San Joaquin Valley, the “breadbasket” of the USA, as it’s often called. And sometimes it’s called the breadbasket of the world. That’d be the small town of Selma, where Levis’ father owned a ranch and had his son labor alongside the migrant workers, on foot and on tractor, learning the family business from the ground up.

The “other side”—what is the other side? That must be Poetry, with a capital “p” in this case, because I’m not referring to the higher degrees Levis received in the subject, first from Fresno State, then Syracuse University and University of Iowa. I’m referring, and I believe Levine is referring, to poetry in the larger sense, that field of exploration and creation, struggle and discovery. See, there’s that word “field” again, and work to be done.

The mention of “self-destructiveness” alludes to the circumstances around Larry Levis’ death, and some goings-on well before. His heart-attack in 1996, coincided with an imprudent dose of cocaine. An accident. Alcohol, cocaine, other substances, together or separate, hadn’t killed him before, so why should they this time around? Because a heart at age 49 isn’t what it was at 25, that’s why, nor is anything else.

The matter has some relevance to this poem, “Fish,” that poem’s central event. I’ve come across a couple readers who didn’t quite understand, thought that law enforcement was just messing with the narrator for no good cause. Perhaps they just skimmed the poem, it happens, but the misreading isn’t helpful or useful. The narrator, the protagonist, is under the influence—judging from the evidence, maybe a barbiturate, a depressive, something in the class of sedative-hypnotics. If it’s alcohol, he’s over the legal limit for driving and not just by two tenths of a point.

I have talked about craft, the deft integration of striking images and agile transitions, but this biographical information, too, colors this piece and deepens our understanding. The central circumstance of this early poem marks the poet’s lifelong engagement with drugs and drink. One could say it presages his death and not exactly be lying—leastwise, it’d be hard for a dissenter to make a case that it doesn’t. At the same time, it’s evidence of his ability to risk his life and tamper with his disposition in all manner of ways but still produce astonishing poems.

Readers, poets, don’t try this at home. You’ll only end up lying wasted, hammered, on a park bench on a cold night. And, in our times, it’s likely that some criminal who preys on the vulnerable will trouble your dream-state before any cop gets the chance.

You won’t even get a good poem out of it for your trouble—anyway, not nearly as good as this one.

***

Years ago, I suggested to a group of students that they’d never come upon another poem—not an accomplished one, anyway, by a recognized, publishing writer—in which a male poet details his utterly shaming domination by another man, with an outcome that offers no retribution, redemption, or moral victory.

One student scoffed at the idea—of course, there were others! I felt a wee bit vexed. I’d be curious to see these others, I said, Go to the Library, find one. (Yes, this occurred in the Age of Libraries.) I said, I predict you won’t be able to turn up even one. I’m not talking about erotica, I said, a consensual situation, such as Allen Ginsberg’s “Please Master, can I kneel at your feet…./Please Master, order me down on the floor….”

I told him, A poem by a woman about the degradation of men doesn’t count. Denise Levertov’s “The Mutes,” “Those groans men use/passing a woman on the street/or the steps of a subway…/Such men most often/look as if groan were all they could do….” That doesn’t count.

And I’m not talking about men brought down by a woman. Keats’ “La Belle Dame Sans Merci” doesn’t count.

I’m talking about a poem where the poet as a grown man is humiliated, dominated, by another grown man (not his father, that’s a different sort of poem) and does not triumph in the end. There is no physical or moral victory. That’s what you won’t find. “Oh, I will,” he said.

“Won’t!”

“Will!”

Next week he entered the class smiling, happy, but not because he’d won the bet. (I wish I’d made a money wager.) He’d had a good time in the library going through volumes of poetry and finding some he liked, so it was a day well spent. Nothing he brought in, as he readily admitted, fit the criteria I’d described. In fact, I didn’t think much of his examples, routine political poems from the 60s, 70s, about confronting cops—a lot of sloganeering, grandstanding. The “I” was always an alpha male, and defiant. Against these, Levis’ poem seemed even rarer and stranger. And braver. Those other ones he turned up made my point. To this day, I’m grateful to that student.

I’d like to widen my challenge. There is no extant poem by a man that details the poet’s own subjugation by another man without a trace of recovered dignity. Or humor! (I just thought of that. Bukowski doesn’t count.) Just to be clear, I’m talking about the poet confessing to having been emasculated. I mean a good poem, not some lines by a hobbyist poet or writer of household verse who’s out there jotting something down right now just to prove me wrong. I say there isn’t one in any language. Someone might claim there is—must be. Fine, I say, go to it. Do your research. I suggest starting with Sanskrit and Aramaic then onto the Greek.

This is all very interesting, but what to make out of this? I’m left with that. So, I’m thinking about it right now—what to make out of this.…

I’ve finished thinking. I make this out of it—that right out of the gate Larry Levis ventured into areas that most other poets instinctively pull back from, and he kept doing that. He never stopped. His poems got longer. In fact, they got long. In later poems, we feel him working his way down, then deeper, ripping away layers and tossing them over his shoulder, trying to touch that place that he had not yet put into words. This early poem has in it, to use Poe’s phrase, a tell-tale heart—it beats with literary and psychic daring together with the mad foolishness that will mark his life and career, and end them both. Both are present. Straight outta the gate.

If Larry Levis were alive today, he’d be mad at me. It’s never wise to reveal to a writer that you like an early work best. Really, better to say you dislike everything they’ve ever written than to hit them with ‘I just love that poem, you know, your best one, that thing you wrote back in 1986.’

“Fish”—what can I say? Probably it’s not his best. He’d evolve others, bigger, more various and layered, but this one continues to fascinate. At age 25, Larry Levis had many poems ahead of him but never wrote another quite like this one.

But then, neither did anyone else.

I like to ask my students, the advanced classes where Larry Levis’ “Fish” is best appreciated—for these poets have probably already attempted what he makes look so very easy—“Where does this poem take place, in the world below, the world above, or this one?”

There is a silence while the group considers the poem from this new point of view then someone will speak up. All three.

Indeed, it moves fluidly, seamlessly, through and around the lower, middle and upper realms, each a chilly landscape glittering with a few sharp details that seem cut with an X-Acto Knife.

“Is it a poem in the high lyric voice or in a natural, speaking voice?” A shorter pause this time, and several respond. Again, both. There’s hardly a word that would stump a fifth grader, not a sentence a sixth grader couldn’t grasp, at least on some level, and the narration rolls forth with seeming spontaneous ease. But “high lyric voice”—oh yes, it’s got that going on. “Once, I thought even through this/I could go quietly as a star turning over and over/in the deep truce of its light….”

Admittedly, the word “truce,” might puzzle some elementary school students, but no more than it will adult readers of poetry. We'll all be puzzled together. And together we'll wonder if the poet might have first written “sluice,” “an act of rinsing or showering with water”— light like a trail of water, yes—then later misread it for “truce.” A ceasefire or cessation of hostilities, he thought (maybe), that’s interesting! In any case, in this mix of images and sounds, both “sluice” and “truce” are sonically gorgeous. I would even have accepted “ruse.”

The poem proceeds in the relaxed, straight-forward manner of a speaking voice yet speaks such things as we have never heard uttered—outside of read-aloud poetry, outside of this poem, on occasions when it’s read aloud. It’s all so simple, and yet the final effect is of mysterious, magisterial gloom.

Sometimes, I invite the group to discover ways in which the images telegraphically connect across many lines, “he feels the huge bones/surrounding my eyes” (and how great a choice is that “huge,” and who among us would’ve thought of it?), with the trout’s “petrified round eyes,” and the “tiny, plastic/skull left on the/dashboard of a junked car” with “the last, filthy/words on the lips/of this shrunken head.” And look how it all fuses at the end, the bone and the stars, the trout pulled from the frozen lake into frozen air, and the gutted “I” (in his present, stunned and anesthetized condition) manhandled by the cop. But this is the head of a man in the hands of a cop, like a decapitated head. That, too, will pass through weird transformations. The “huge” bones shrink in the cop’s hands, become, in the imagination of the speaker, a knickknack discarded along with the junked car. Finally, it occupies the moon, but it’s a desolate head encircled by its own death.

Were that all it’d be plenty, but there’s more, a little move the poem makes half way through, a leap across the urban landscape—the middle world, this one—in a moment of sudden, unwilled seeing (the eye pried open): “the cold/night rippling with neons,/and the razor blades/of the poor,/and the torn mouths on posters.”

Is it dazzling or squalid? Is it earthy or metaphysical? “…pines rise into darkness…trout freeze into bits of stars…the razor blades of the poor…” Both, always both, sinking and rising through those three uneasy landscapes. Dreamscapes.

Among the icy strata only one thing burns, and one thing is branded by that burning.

I can think of another paradox, another opposition, though I’ve never tried this one on my students. Even as the narrator lays bare his humiliation, his utter debasement, the poet ascends into the empyrean. After all, Levis wrote this tour de force, “Fish,” when he was only 25. It announced his arrival, a poet whose name, in certain circles, would eventually take on some of the attributes of lore and legend.

***

In Michele Poulos’ documentary about Larry Levis, A Late Style of Fire, Philip Levine offers this conjecture, “I don’t think he saw it as self-destructiveness. I think he saw it as the pursuit of Duende, if we want to use Lorca’s term, and there was a constant struggle between creation and destruction, and he wanted to be at the center of that, to get what was best for his poetry.”

He's speaking of his student then lifelong friend, the poet whose artistic cachet— mystique—had begun to take hold well before his sudden death. “He was born on one side,” says Levine, “but his soul grew up on the other.”

That “one side” would be the agricultural trade, the orchards and fields of the San Joaquin Valley, the “breadbasket” of the USA, as it’s often called. And sometimes it’s called the breadbasket of the world. That’d be the small town of Selma, where Levis’ father owned a ranch and had his son labor alongside the migrant workers, on foot and on tractor, learning the family business from the ground up.

The “other side”—what is the other side? That must be Poetry, with a capital “p” in this case, because I’m not referring to the higher degrees Levis received in the subject, first from Fresno State, then Syracuse University and University of Iowa. I’m referring, and I believe Levine is referring, to poetry in the larger sense, that field of exploration and creation, struggle and discovery. See, there’s that word “field” again, and work to be done.

The mention of “self-destructiveness” alludes to the circumstances around Larry Levis’ death, and some goings-on well before. His heart-attack in 1996, coincided with an imprudent dose of cocaine. An accident. Alcohol, cocaine, other substances, together or separate, hadn’t killed him before, so why should they this time around? Because a heart at age 49 isn’t what it was at 25, that’s why, nor is anything else.

The matter has some relevance to this poem, “Fish,” that poem’s central event. I’ve come across a couple readers who didn’t quite understand, thought that law enforcement was just messing with the narrator for no good cause. Perhaps they just skimmed the poem, it happens, but the misreading isn’t helpful or useful. The narrator, the protagonist, is under the influence—judging from the evidence, maybe a barbiturate, a depressive, something in the class of sedative-hypnotics. If it’s alcohol, he’s over the legal limit for driving and not just by two tenths of a point.

I have talked about craft, the deft integration of striking images and agile transitions, but this biographical information, too, colors this piece and deepens our understanding. The central circumstance of this early poem marks the poet’s lifelong engagement with drugs and drink. One could say it presages his death and not exactly be lying—leastwise, it’d be hard for a dissenter to make a case that it doesn’t. At the same time, it’s evidence of his ability to risk his life and tamper with his disposition in all manner of ways but still produce astonishing poems.

Readers, poets, don’t try this at home. You’ll only end up lying wasted, hammered, on a park bench on a cold night. And, in our times, it’s likely that some criminal who preys on the vulnerable will trouble your dream-state before any cop gets the chance.

You won’t even get a good poem out of it for your trouble—anyway, not nearly as good as this one.

***

Years ago, I suggested to a group of students that they’d never come upon another poem—not an accomplished one, anyway, by a recognized, publishing writer—in which a male poet details his utterly shaming domination by another man, with an outcome that offers no retribution, redemption, or moral victory.

One student scoffed at the idea—of course, there were others! I felt a wee bit vexed. I’d be curious to see these others, I said, Go to the Library, find one. (Yes, this occurred in the Age of Libraries.) I said, I predict you won’t be able to turn up even one. I’m not talking about erotica, I said, a consensual situation, such as Allen Ginsberg’s “Please Master, can I kneel at your feet…./Please Master, order me down on the floor….”

I told him, A poem by a woman about the degradation of men doesn’t count. Denise Levertov’s “The Mutes,” “Those groans men use/passing a woman on the street/or the steps of a subway…/Such men most often/look as if groan were all they could do….” That doesn’t count.

And I’m not talking about men brought down by a woman. Keats’ “La Belle Dame Sans Merci” doesn’t count.

I’m talking about a poem where the poet as a grown man is humiliated, dominated, by another grown man (not his father, that’s a different sort of poem) and does not triumph in the end. There is no physical or moral victory. That’s what you won’t find. “Oh, I will,” he said.

“Won’t!”

“Will!”

Next week he entered the class smiling, happy, but not because he’d won the bet. (I wish I’d made a money wager.) He’d had a good time in the library going through volumes of poetry and finding some he liked, so it was a day well spent. Nothing he brought in, as he readily admitted, fit the criteria I’d described. In fact, I didn’t think much of his examples, routine political poems from the 60s, 70s, about confronting cops—a lot of sloganeering, grandstanding. The “I” was always an alpha male, and defiant. Against these, Levis’ poem seemed even rarer and stranger. And braver. Those other ones he turned up made my point. To this day, I’m grateful to that student.

I’d like to widen my challenge. There is no extant poem by a man that details the poet’s own subjugation by another man without a trace of recovered dignity. Or humor! (I just thought of that. Bukowski doesn’t count.) Just to be clear, I’m talking about the poet confessing to having been emasculated. I mean a good poem, not some lines by a hobbyist poet or writer of household verse who’s out there jotting something down right now just to prove me wrong. I say there isn’t one in any language. Someone might claim there is—must be. Fine, I say, go to it. Do your research. I suggest starting with Sanskrit and Aramaic then onto the Greek.

This is all very interesting, but what to make out of this? I’m left with that. So, I’m thinking about it right now—what to make out of this.…

I’ve finished thinking. I make this out of it—that right out of the gate Larry Levis ventured into areas that most other poets instinctively pull back from, and he kept doing that. He never stopped. His poems got longer. In fact, they got long. In later poems, we feel him working his way down, then deeper, ripping away layers and tossing them over his shoulder, trying to touch that place that he had not yet put into words. This early poem has in it, to use Poe’s phrase, a tell-tale heart—it beats with literary and psychic daring together with the mad foolishness that will mark his life and career, and end them both. Both are present. Straight outta the gate.

If Larry Levis were alive today, he’d be mad at me. It’s never wise to reveal to a writer that you like an early work best. Really, better to say you dislike everything they’ve ever written than to hit them with ‘I just love that poem, you know, your best one, that thing you wrote back in 1986.’

“Fish”—what can I say? Probably it’s not his best. He’d evolve others, bigger, more various and layered, but this one continues to fascinate. At age 25, Larry Levis had many poems ahead of him but never wrote another quite like this one.

But then, neither did anyone else.

Suzanne Lummis has been variously associated with the Los Angeles based Stand-Up Poetry movement of the 90s, the Fresno Poets, and poetry noir. Poetry.la produces her video series exploring the connection between contemporary poems and the sensibilities of classic film noir. Her poetry has appeared in New Ohio Review, The Antioch Review, American Journal of Poetry, Plume, The New Yorker, and in three Knopf “Everyman’s Library” Pocket Poets anthologies. She was a 2018-19 COLA (City of Los Angeles) fellow, and with that endowment evolved a poem containing history, Tweets from Hell, soon to appear as a 19th-century-style political pamphlet.