Nomadic Breathing: Translating the Poetry of Jean Portante by Zoë Skoulding

What does it mean to translate the poetry of Jean Portante, when his work is already an act of translation? His poems are a continuous process of migration, refusing a stable point of authorial origin just as much as a fixed end point of reception. As his etymological column 'Les Mots Voyageurs' in Le Jeudi stresses, words are always on the move from somewhere else: so too the poem.[i] Translation is therefore an extension of a linguistic movement that is already present, and this intertextuality is further intensified by the poet-to-poet exchange of our work. My translation of his poems, In Reality: Selected Poems, published in 2013,[ii] is also a continuation of our conversations about poetry ; it encompasses the ways in which these conversations have inflected my own poems, our joint translation of the American poet Jerome Rothenberg into French,[iii] and Portante's translations of my poems into French, through which I have learned about his process as a translator first-hand.[iv] The activity of writing poetry is, in these ways, inseparable from the activity of translation. For Portante, translation is one of the many forms of nomadic movement that are central to his practice as a fiction writer as much as his poetry, which is informed by a biographical background of historical family migration, as well as a dynamic tension between the orality of his mother tongue, Italian, and written French. In navigating the passage between places, as well as the passage between memory and forgetting, how can translation respond to a poetics that is constantly on the move?

I is many others

My first point of connection with Portante's work was through that of another poet from Luxembourg, Pierre Joris, who is also an expatriate and writes in a language that is not his first, in his case the English of the United States. Joris's work as a poet, anthologist and theorist had long been important to me, so when I discovered Portante's work, by chance at a poetry festival in Nicaragua, and found that they were old friends and compatriots, I had a reference point as I began to imagine a version of Portante in English. If this anecdotal aside seems at a remove from a traditional view of translation as an act of linguistic fidelity to a source text, it is one that explains how, as a poet, I have also come to be a translator. The relationship between the movement of translation and the unfixing of the self is articulated in Joris’s “Nomad Manifesto", in which he writes: "Rimbaud accurately said [. . .] 'I is another.' We now have to say : 'I is many others'. A nomadic poetics will thus explore ways in which to make — & think about — a poetry that takes into account not only the manifold of languages & locations but also of selves each one of us is constantly becoming."[v]

Joris's challenge to poets is that poetic practice should be infused by multiple languages; it is through this vision that I came to discover Portante's work. The nomadic and the 'mot voyageur' may appear to suggest a romantic individualism, but the context of travel for both Joris and Portante is far from the idealised freedom of the tourist. Joris uses the term 'nomadic' with personal knowledge of the Maghreb and an understanding of the environmental pressures that drive traditional nomadic movement, while Portante's linguistic nomadism is rooted in his family history of European economic migration. To say 'I is many others' is, therefore, to acknowledge the social and political reality of multiple perspectives. Rimbaud's 'long, immense et raisonné dérèglement de tous les sens'[vi] is often read incorrectly in the anglophone world, as the English poet Sean Bonney observes, as 'a simple recipe for personal excess', whereas in the revolutionary context of Rimbaud's poetry we should see a derangement of the social senses, in which '"I" becomes "another" as in the transformation of the individual into the collective ... '.[vii] In the context of translation, this adds a further dimension, since if the poetic subject is constantly transforming itself into others, fidelity is not a helpful concept ; the translation, too, must become nomadic and plural, taking the 'many others' into account.

Whale translation

Although Joris and Portante are very different poets, they both destabilize the major languages in which they write by insisting on their plural nature. The importance of this is well understood in multilingual Luxembourg, but it has more radical implications in France, for Portante, in the USA for Joris, or in the UK, destination of my translations of Portante's poems, which is increasingly and sadly denying its multilingual European kinship. Recent events in the UK, such as the upsurge in racism that accompanied the referendum on leaving the EU, reveal the political urgency of a poetry that thinks translation, and that is itself translation. By contesting linguistic boundaries it can also contest the politics that insists on singular, bounded, identities. Poetry articulates an exchange of language and difference that happens not at the border or the ocean, but in the split second between one breath and another. Where I write, in English but in the bilingual context of Wales, such a provisional coexistence of languages is particularly resonant, and this too partly explains how I came to translate Portante's work and why it is published in Wales. His poetry has, of course, been translated into many other languages, and it returns constantly to an interest in language as irreducibly multiple. As he writes: 'there isn’t ONE language in my writing. What you see is the French language, a little disordered but on the whole correct, I mean orthographically, morphologically and syntactically speaking. What isn’t seen, what only exists inside, "lungs" [poumonne] the plurality of languages, the mother tongue and others, without revealing itself.’[viii]

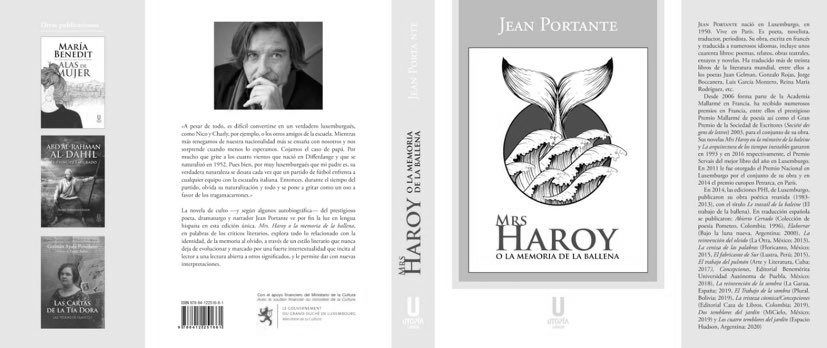

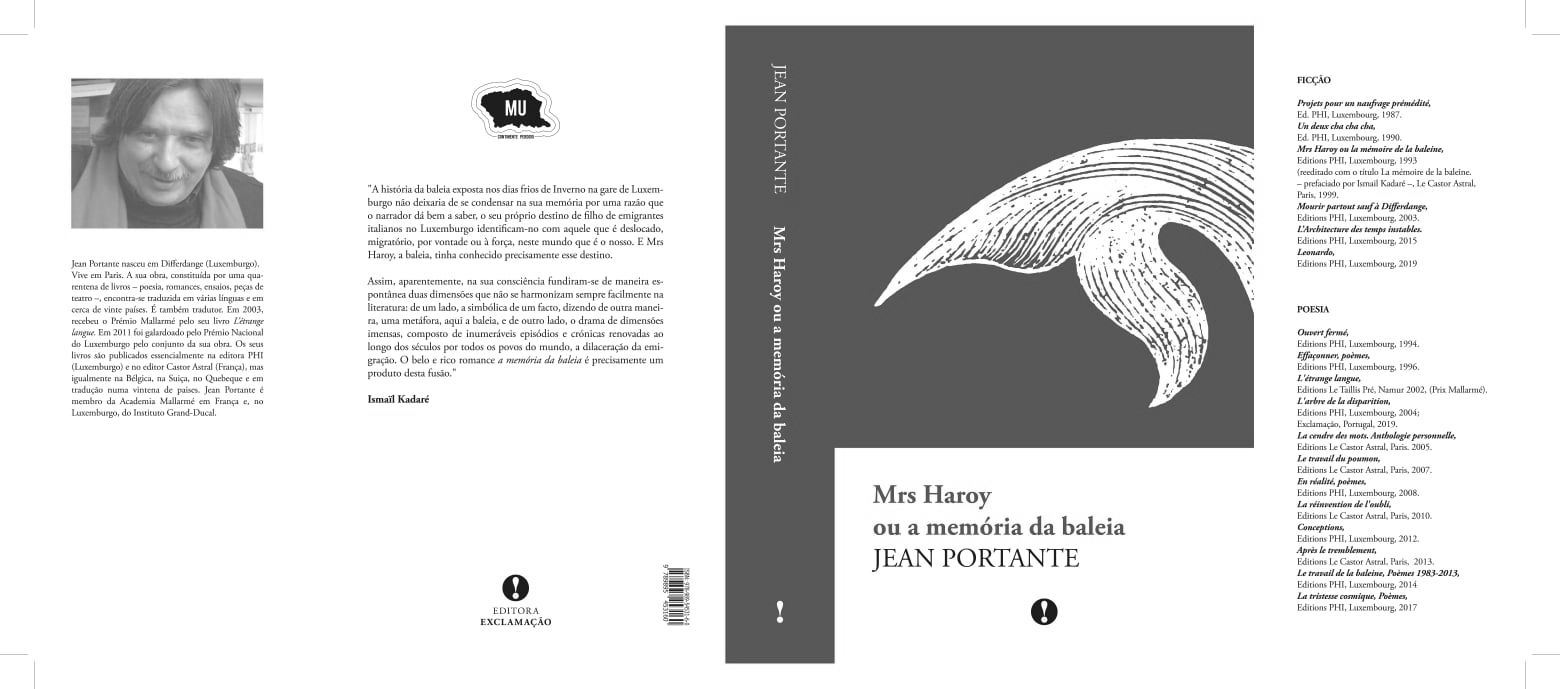

Editora Exclamação, 2019

The metaphor of the whale recurs in Portante’s writings, in both poetry and prose, as an image of concealed plurality. The whale appears to be at home in its aquatic element but its hidden lung is a reminder of its evolution from a terrestrial existence and an emblem of its secret doubleness. Of the relationship between French and Italian in his work, he writes: 'it is necessary to erase the language one sees in order to read the plurality of languages' ; that is, the destruction of one language by another in his practice reveals the multiplicity already inherent in any language.[ix] He refers to this process as effaconnement, which suggests both erasing and creation.[x] In this paradoxical relationship of languages there are echoes of Jacques Derrida in Le monolingualisme de l'autre, where he confesses: 'Je n'ai qu'une langue, ce n'est pas la mienne,' a statement that reflects the position of all linguistic subjects, since language is never owned, but is especially visible in the case of the nomadic speaker.[xi] 'On ne parle jamais qu'une seule langue – ou plutôt un seul idiome. 2. On ne parle jamais une seule langue – ou plutôt il n'y a pas d'idiome pur.'[xii] Portante's work asserts the plurality of languages while holding to French as the language that is both his and not his. As in the case of Derrida, there is a gesture towards the abolition of linguistic frontiers that is not far-fetched when viewed in the long etymological time span suggested by the whale's evolutionary history. At the same time, the poem, for Portante is always a distinct linguistic trajectory carved out within a language, the poem's path one of many possible variants within a language, since form foregrounds the play of signification and its arbitrary relation to sound.

Derrida's insight is important to translation because it reveals the slipperiness of defining a single source language, hence the difficulty of traditional notions of fidelity. He argues that there can be no metalanguage because one cannot speak of a language other than in that language, yet a language can, within itself, contain traces of the elsewheres and possibilities of translation: 'Des effets de métalangage, des effets ou des phénomènes relatifs, à savoir des relais de métalangage “dans” une langue y introduisent déjà de la traduction, de l'objectivation en cours. Ils laissent trembler à l'horizon, visible et miraculeux, spectral mais infiniment désirable, le mirage d'une autre langue.'[xiii] Texts are already infected with translation, full of complex intertextualities, before the translator begins translating, even before the source poem is written. The elusive relationship between languages cannot be described by simply placing a translation alongside a source text, since the act of translation takes place in a linguistic environment that is as mobile and oceanic as the whale's.

In discussion with Joris, Portante has talked about his decision in the early 1980s to write in French: 'I sensed, very much under your influence at the time and reading work (especially by Americans) that you suggested to me, that the chosen language would not permit me to go very far, and that I would have to make it tremble inside, to unsettle it by secretly introducing one or several Trojan horses. Yet in translation the Trojan horses often tend to disappear.'[xiv]

There are parallels here with the abrogation and appropriation of language in a post-colonial context, a political stance in which the illusory standards of language of colonial control must be disrupted in order to bear the weight of different cultural experiences.[xv] In Portante's case, this abrogation is not a post-colonial response to French but, rather, one that makes visible certain class histories of European worker migration. The military image of the Trojan horse reveals what is at stake in the breathing or 'lunging' of the whale : it is not, or at least not only, a personal nostalgia for a lost past but a deeper disruption of the limits of statehood through an insistence on language's mobility. These specific linguistic relationships become less visible in translation, but they invite reflection on potential equivalence. In bringing Portante's work into English I discovered different areas of friction and resistance that it was important not to smooth over.

Echoing strangeness

Having outlined some of the background to translating Portante's work as well as my impetus for doing so, I will turn to my own translations and the process involved. The friction I have mentioned between Italian and French is one that resists easy assimilation into another language. Breathing usually happens unconsciously, without thought, and since there is no sounded word without breath, it is the beginning of every poem. In Portante's poetry, however, as for the whale, breathing prevents a completely fluid immersion in its environment; it remains a point of difference. As we began to discuss my draft translations, my most frequent question was: 'Does this sound as strange in French as it does in English?' The answer was almost inevitably affirmative, and the challenge was then not to domesticate but to allow the same Trojan horse dynamic to run through the English and make in it an echoing strangeness. Strangeness, in this collaborative context of translation, is a value that is mutually understood in terms of juxtaposition that prevents language from being transparent, but it also carries with it the suggestion of foreignness.

Following Lawrence Venuti's strictures against the invisibility of translation I have tried not to smooth the poems into an existing aesthetic in English, but to allow them to suggest a different one that would transform my own writing and my own language.[xvi] An example of this process is 'LA FIÈVRE DES CHOSES' from Portante's 2010 collection La réinvention de l'oubli:

Parmi les fatigues qui restent

laquelle garderais-tu

si l’arbre venait à disparaître:

si du tronc comme d’une ignorance de plus

ou de la brume tout autour se détachait

LA FIÈVRE DES CHOSES :

si chaque racine avait sa fatigue

et son tronc

qu’en garderais-tu :

et si à chaque racine était fixée une étiquette :

et si l’étiquette disait que ce qui disparaît

est ce qui reste quand tout autour

se détache des choses la fièvre

qu’en garderais-tu.

Among the remaining exhaustions

which one would you keep

if the tree came to disappear:

if breaking away from the trunk as if from

one more unknown or from surrounding mist was

THE FEVER OF THINGS:

if each root had its exhaustion

and its trunk

what would you keep:

if on each root was fixed a tag:

and if the tag said what is disappearing

and what remains when all around

the fever breaks away from things

what would you keep.[xvii]

The movement of translation here is inseparable from the process of definition that takes place in the source text. Relations between the tree trunks, the fever and the explanatory tags of language are unstable, but established in the terms of the poem through repetition, as so often in Portante's poems where a personal symbolism charges words with remade meaning. This is the mot voyageur in action, since by the end of the poem 'fever' and 'exhaustion' have taken on a meaning peculiar to this particular poem and its probing of memory and language. Rather than applying to a person, as might usually be expected, these symptoms are set in a landscape alongside things and the words for them ; they seem to behave independently in ways that would normally be impossible. The repetitive pattern establishes a tenuous but insistent logic that exists in sound, and in the memory of the poem, rather than any external reference point. This is the process whereby the poet writes not in French, Italian or English, but in an adaptation of Lacan, what Portante calls malangue, the language of the individual poet. He comments in an interview: 'Je pense que si un écrivain n’écrit pas dans sa propre langue, que d’ailleurs dans la psychanalyse on appelle une "malangue" – chacun a une "malangue" – si on n’écrit pas dans sa "malangue" alors on écrit dans la langue d’un autre et on n’est plus dans la littérature.'[xviii] We have considered the idea that, since we are both poets, my translations are not from French to English, but from the language of Jean Portante to the language of Zoë Skoulding. This may to some extent be the case, but a Portante poem does not sound like one of mine, and I am more interested in following the contours of a different voice than assimilating it to my own. That is, the translator, as much as the poet, may be in search of a plural identity.

Rhythm in discourse

In translating, the rhythm very often carries across into English because the poems are driven by speech patterns rather than metrical arrangement. There is a rhetorical structure in the build-up of conditional clauses, resolved with a question. Here, as so often in Portante's poems, there is a conversational feel, but it is also disrupted by the unexpected punctuation and capitalisation, and by forms of personification foregrounded by unusual choices of syntax. In the rhythmical subjectivity established in these poems, there is a tension between orality and writing that mirrors the tension between Italian and French. Since I do not speak Italian, it is by and large this friction between the oral and the written that alerts me to the poem's hidden Italian lung.

At this point it is helpful to turn to the poet and theorist Henri Meschonnic's observations on rhythm in poetry to clarify some of the issues at stake. He observes that rhythm in poetry is fundamentally unlike rhythm in music since it is never an abstract metrical pattern but always part of language as discourse.[xix] Meschonnic draws on Benveniste's observation that in pre-Platonic thinking on rhythm there is an opposition between rhuthmos (organisation of moving things) and skhêma (organisation of immobile things). Benveniste reveals a means of approaching rhythm not in its later sense of regular pattern but as 'la forme improvisée, momentanée, modifiable.'[xx] This consideration of rhythm as movement becomes, for Meschonnic, connected with a subjectivity that moves in and through language. The poem is the movement of the subject as language being unmade and remade anew ; rhythm is an individual movement, in contrast to the constraints of metre. In this view, language and life have the potential to be mutually transformative: 'Contre toutes les poétisations, je dis qu'il y a un poème seulement si une forme de vie transforme une forme de langage et si réciproquement une forme de langage transforme une forme de vie.'[xxi] This emphasis on poetry as a form of movement helps to clarify Portante's project, which explores the implications of writing understood as an individual and transformative linguistic trajectory. The ' Italian lung' of his work may be felt in lines like the following, with their rolling metrical pattern in which stressed syllables foreground the beginning of the line:

si du tronc comme d’une ignorance de plus

ou de la brume tout autour se détachait

LA FIÈVRE DES CHOSES :[xxii]

This is a form of resistance to French, where a more typical sonic structure would be a rapid movement towards an emphasis at the end. Rhythm, in Meschonnic's account, can be a means of describing that oscillation between languages that in Portante's case is a product of particular social and historical circumstances. He transforms the French language by breathing Italian through it, and in doing so, like every bilingual speaker, continues the long migration of all peoples and all languages, articulating a subjectivity that is simultaneously plural and minutely individual.

Listening to the 'voice' of the poem, therefore, involves paying attention to sound, but bearing in mind that the poem is already nomadic, it is important to catch its movement rather than impose on it a fixed point that must be replicated in translation. When I am translating I am not, for example, listening for 'the sound of sense' as Robert Frost puts it.[xxiii] For Frost, 'sense' is dependent on a shared context in which conversational cadence can carry meaning. In Portante's work the vitality comes from exactly the opposite: the space between languages, the break in sense as the cadences of Italian are heard through French. Within the source text there is already a conflict between sense as meaning and the sense-impression of sound; it is this conflict that creates a sense of direction and movement. For Meschonnic, the work of translation involves attending to the ear, and the range of syntactical and prosodic effects that shape meaning. His emphasis on the primacy of sound in translation might be seen as replacing fidelity to sense with an equally unattainable fidelity to sound, but he also comments on the spatial aspects of rhythm in ways that are useful in a reading of Portante, for example : 'Non, les mots ne sont pas faits pour désigner les choses. Ils sont là pour nous situer parmi les choses.'[xxiv] His emphasis on the materiality of sound reveals that words are also things. Rhythm is therefore a spatial movement, a process of situating, that may be answered if not reproduced in translation.

Breathing and transformation

There are repetitions in Portante's work in words and images carried from one book to the next; they build on previous articulations and resist dispersal. However, the sound of the poem is not based on metrical repetition, but an onward movement in which words and phrases are subject to continuous transformation. This can be seen in the following poem, which creates its own accretive context:

Dans l’œil de l’oiseau d’automne

avant qu’il ne parte

le jour paraît long :

long paraît aussi mais cela

nous ne le savons plus

le souffle qui tout autour

éteint et rallume les bougies :

nous creusons des métropolitains

dans leur cire

et aboutissons à des nuages

dont les contours perdent leur couleur

quand

TANT DE LUMIÈRE

y pénètre :

tout va vers l’absence

et à mesure que s’approche la clarté

le maintenant de ce qui reste

ressemble à l’oiseau d’automne

prêt à s’envoler :

nous le regardons

perché sur le vieux poteau noir

qui en a vu d’autres

et aimons nous dire

qu’entre celui qui en automne part

et l’autre qui au printemps reviendra s’y poser

il n’y a plus aucune ressemblance :

non que le voyage éteigne en eux

les longues bougies de l’oubli :

non que des longues bougies de l’oubli

comme d’un vieux poteau noir

dépende ce que l’automne a caché

dans l’œil de l’oiseau du printemps

avant qu’il ne parte.

In the eye of autumn’s bird

before it leavesthe day seems long

and it seems long too

though we no longer know this

the breath that all around

snuffs out and relights the candles:

we dig tunnels

in their wax

and end up at clouds

that lose their colours at the edges

when

SO MUCH LIGHT

gets in:

everything moves towards absence

and as clarity approaches

the now of what remains

looks like autumn's bird

ready to fly away:

we watch it

perched on the old black post

that has seen it all before

and like to say to ourselves

that between the one leaving in autumn

and the one that will come back to land there in spring

there's no longer any resemblance:

not that the journey snuffs out in them

the long candles of forgetting

not that on the long candles of forgetting

as if on an old black post

there hangs what autumn has hidden

in the eye of spring’s bird

before it leaves. [xxv]

There are moments of return but each repetition creates change ; in a rhythmical sense the migratory pattern is not a to and fro repetition but a continuous process of change, since what we come back to is full of hidden difference. The ambiguous qualities of breath are particularly in evidence in the sound of this poem, as it moves syntactically from one suspension to another. Breath is a central image, too, as it snuffs out and relights candles, which in the play between French and Italian, are also lies, a point explained in the earlier collection Le travail du poumon: 'en écrivant bougie, l'animal du dedans a glissé en elle l'italien bugia. Or, bugia signifie mensonge, et va donc, alors que la bougie sert l'éclairage, vers l'absence de lumière. Vers l’obscur.'[xxvi]

A pun like this cannot be translated, so it moves further into darkness with translation. The significance of the candle as an ambiguous illumination that is also a concealment is inevitably and ironically concealed by the translation. However, this may not be a bad thing. The tunnels dug in wax and the fading colours refer back to a moment in Fellini's Roma, a reference explained in the 'Mode d'Emploi ' of La réinvention de l'oubli : at one point in the film the process of building the metro system in Rome uncovers ancient frescoes, but at the moment when they are exposed they fade instantly. Most commentators on the film have attributed the fading to contact with air, but for Portante it is light, the rolling cameras that obliterate memory as they reveal it. When too much light gets in, the flickering of secret presence is lost. There is a parallel with the secret Italian lung, as Portante describes the sensation of reading his own work in Italian translation in the following terms: 'In seeing my poems, and also my prose returned to the maternal language by another's hand, it was as if this other was stealing the inside lung of my writing to expose it to the open air. Suddenly, the underground became the surface, and all the journey that linked the inside and the outside had disappeared.’[xxvii]

What might appear to be complete translation is in fact, therefore, a betrayal of the poem's dynamic between concealment and revelation. This particular kind of disappearance does not arise with translation into English ; the pun may not be translatable but the 'long candles of forgetting' are sufficiently out of line with colloquial English expression to signal the presence of imagery that cannot be made fully transparent.

If my translations of these poems do not arrive in English with a sense of complete resolution, this is because I read in Portante's work a poetics that depends on a continuing movement through multiple personal histories as well as the collaboration of translation. The rhythmical sounding of the poem places it between languages, between speakers and between breathing beings; like breathing, the poem is a negotiation between hidden interiors and the open air of shared discourse. To return to Joris and his nomadic poetics, English translation adds one more element to a body of work that is already linguistically multiple, one more journey to a poetry that is already on the move.

[i] Jean Portante, Les mots voyageurs [rubrique régulière] Le Jeudi. - n°1 ff. (2009 – 2019).

[ii] Jean Portante, In Reality: Selected Poems, trans. from French by Zoë Skoulding, Bridgend. Seren, 2013.

[iii] Jerome Rothenberg, Pologne 1931, trans. from English by Jean Portante and Zoë Skoulding, Paris, éd. Caractères, 2013.

[iv] Zoë Skoulding, Teint: For the Bièvre / Teint Pour la Bièvre, trans. from English by Jean Portante, Hafan Books, 2016.

[v] Pierre Joris, A Nomad Poetics: Essays, Connecticut, Wesleyan University Press, 2003, pp. 43-44.

[vi] Arthur Rimbaud, Arthur Rimbaud, Lettre à Paul Demeny, 15 mai 1871 in Rimbaud: Complete Works, Selected Letters, a Bilingual Edition. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2010, p. 372.

[vii] Sean Bonney, Letters Against the Firmament, London, Enitharmon, 2015, p. 140.

[viii] Pierre Joris and Jean Portante, « Whales, Ghosts and Nomads: A Dialogue », Poetry Wales 46.3. 2011, p. 10.

[ix]Joris and Portante, 2011, p. 11.

[x]Joris and Portante, 2011, p. 11.

[xi] Jacques Derrida, Le monolingualisme de l'autre. p. 13.

[xii] Derrida, pp. 21-22.

[xiii] Derrida, p. 44.

[xiv] Joris and Portante, p. 11.

[xv] Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths and Helen Tiffin, The Empire Writes Back: Theory and Practice in Post-colonial Literatures. London, Psychology Press, 2002, pp. 37-38.

[xvi] Lawrence Venuti, The Translator's Invisibility. London, Routledge, 1995.

[xvii] Jean Portante, trans Zoë Skoulding, In Reality: Selected Poems. Bridgend, Seren, 2013, pp. 52-53.

[xviii] https://poesiemuziketc.wordpress.com/2013/04/24/poete-interview-avec-jean-portante-sur-le-metier-du-poete/ Accessed 03.06.18.

[xix] Henri Meschonnic Critique du rythme p.121.

[xx] E. Benveniste, « La notion de “rythme” dans son expression linguistique » (1951), Problèmes de linguistique générale. Paris, Gallimard, 1966.

[xxi] Henri Meschonnic, « Manifeste pour un parti du rythme », http://www.berlol.net/mescho2.htm,1999. Accessed 03.06.18.

[xxii] IR p. 52.

[xxiii] In a letter of 1913, Frost comments: « The best place to get the abstract sound of sense is from voices behind a door that cuts off the words… it is the abstract vitality of our speech. » In his view, even if the words behind the door are indecipherable, cadence can be understood. However, this depends on an underlying familiarity with a shared context. Frost, R. (1913). Letter to John T. Bartlett, July 4, 1913. In Selected Letters of Robert Frost, ed. L. Thompson. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964, pp. 79-81.

[xxiv] Meschonnic, « Manifeste pour un parti du rythme ».

[xxv] IR pp. 64-65.

[xxvi] Jean Portante, Le travail du poumon. Paris, Le Castor Astral, 2007.

[xxvii] Joris and Portante, p. 14.

I is many others

My first point of connection with Portante's work was through that of another poet from Luxembourg, Pierre Joris, who is also an expatriate and writes in a language that is not his first, in his case the English of the United States. Joris's work as a poet, anthologist and theorist had long been important to me, so when I discovered Portante's work, by chance at a poetry festival in Nicaragua, and found that they were old friends and compatriots, I had a reference point as I began to imagine a version of Portante in English. If this anecdotal aside seems at a remove from a traditional view of translation as an act of linguistic fidelity to a source text, it is one that explains how, as a poet, I have also come to be a translator. The relationship between the movement of translation and the unfixing of the self is articulated in Joris’s “Nomad Manifesto", in which he writes: "Rimbaud accurately said [. . .] 'I is another.' We now have to say : 'I is many others'. A nomadic poetics will thus explore ways in which to make — & think about — a poetry that takes into account not only the manifold of languages & locations but also of selves each one of us is constantly becoming."[v]

Joris's challenge to poets is that poetic practice should be infused by multiple languages; it is through this vision that I came to discover Portante's work. The nomadic and the 'mot voyageur' may appear to suggest a romantic individualism, but the context of travel for both Joris and Portante is far from the idealised freedom of the tourist. Joris uses the term 'nomadic' with personal knowledge of the Maghreb and an understanding of the environmental pressures that drive traditional nomadic movement, while Portante's linguistic nomadism is rooted in his family history of European economic migration. To say 'I is many others' is, therefore, to acknowledge the social and political reality of multiple perspectives. Rimbaud's 'long, immense et raisonné dérèglement de tous les sens'[vi] is often read incorrectly in the anglophone world, as the English poet Sean Bonney observes, as 'a simple recipe for personal excess', whereas in the revolutionary context of Rimbaud's poetry we should see a derangement of the social senses, in which '"I" becomes "another" as in the transformation of the individual into the collective ... '.[vii] In the context of translation, this adds a further dimension, since if the poetic subject is constantly transforming itself into others, fidelity is not a helpful concept ; the translation, too, must become nomadic and plural, taking the 'many others' into account.

Whale translation

Although Joris and Portante are very different poets, they both destabilize the major languages in which they write by insisting on their plural nature. The importance of this is well understood in multilingual Luxembourg, but it has more radical implications in France, for Portante, in the USA for Joris, or in the UK, destination of my translations of Portante's poems, which is increasingly and sadly denying its multilingual European kinship. Recent events in the UK, such as the upsurge in racism that accompanied the referendum on leaving the EU, reveal the political urgency of a poetry that thinks translation, and that is itself translation. By contesting linguistic boundaries it can also contest the politics that insists on singular, bounded, identities. Poetry articulates an exchange of language and difference that happens not at the border or the ocean, but in the split second between one breath and another. Where I write, in English but in the bilingual context of Wales, such a provisional coexistence of languages is particularly resonant, and this too partly explains how I came to translate Portante's work and why it is published in Wales. His poetry has, of course, been translated into many other languages, and it returns constantly to an interest in language as irreducibly multiple. As he writes: 'there isn’t ONE language in my writing. What you see is the French language, a little disordered but on the whole correct, I mean orthographically, morphologically and syntactically speaking. What isn’t seen, what only exists inside, "lungs" [poumonne] the plurality of languages, the mother tongue and others, without revealing itself.’[viii]

Editora Exclamação, 2019

The metaphor of the whale recurs in Portante’s writings, in both poetry and prose, as an image of concealed plurality. The whale appears to be at home in its aquatic element but its hidden lung is a reminder of its evolution from a terrestrial existence and an emblem of its secret doubleness. Of the relationship between French and Italian in his work, he writes: 'it is necessary to erase the language one sees in order to read the plurality of languages' ; that is, the destruction of one language by another in his practice reveals the multiplicity already inherent in any language.[ix] He refers to this process as effaconnement, which suggests both erasing and creation.[x] In this paradoxical relationship of languages there are echoes of Jacques Derrida in Le monolingualisme de l'autre, where he confesses: 'Je n'ai qu'une langue, ce n'est pas la mienne,' a statement that reflects the position of all linguistic subjects, since language is never owned, but is especially visible in the case of the nomadic speaker.[xi] 'On ne parle jamais qu'une seule langue – ou plutôt un seul idiome. 2. On ne parle jamais une seule langue – ou plutôt il n'y a pas d'idiome pur.'[xii] Portante's work asserts the plurality of languages while holding to French as the language that is both his and not his. As in the case of Derrida, there is a gesture towards the abolition of linguistic frontiers that is not far-fetched when viewed in the long etymological time span suggested by the whale's evolutionary history. At the same time, the poem, for Portante is always a distinct linguistic trajectory carved out within a language, the poem's path one of many possible variants within a language, since form foregrounds the play of signification and its arbitrary relation to sound.

Derrida's insight is important to translation because it reveals the slipperiness of defining a single source language, hence the difficulty of traditional notions of fidelity. He argues that there can be no metalanguage because one cannot speak of a language other than in that language, yet a language can, within itself, contain traces of the elsewheres and possibilities of translation: 'Des effets de métalangage, des effets ou des phénomènes relatifs, à savoir des relais de métalangage “dans” une langue y introduisent déjà de la traduction, de l'objectivation en cours. Ils laissent trembler à l'horizon, visible et miraculeux, spectral mais infiniment désirable, le mirage d'une autre langue.'[xiii] Texts are already infected with translation, full of complex intertextualities, before the translator begins translating, even before the source poem is written. The elusive relationship between languages cannot be described by simply placing a translation alongside a source text, since the act of translation takes place in a linguistic environment that is as mobile and oceanic as the whale's.

In discussion with Joris, Portante has talked about his decision in the early 1980s to write in French: 'I sensed, very much under your influence at the time and reading work (especially by Americans) that you suggested to me, that the chosen language would not permit me to go very far, and that I would have to make it tremble inside, to unsettle it by secretly introducing one or several Trojan horses. Yet in translation the Trojan horses often tend to disappear.'[xiv]

There are parallels here with the abrogation and appropriation of language in a post-colonial context, a political stance in which the illusory standards of language of colonial control must be disrupted in order to bear the weight of different cultural experiences.[xv] In Portante's case, this abrogation is not a post-colonial response to French but, rather, one that makes visible certain class histories of European worker migration. The military image of the Trojan horse reveals what is at stake in the breathing or 'lunging' of the whale : it is not, or at least not only, a personal nostalgia for a lost past but a deeper disruption of the limits of statehood through an insistence on language's mobility. These specific linguistic relationships become less visible in translation, but they invite reflection on potential equivalence. In bringing Portante's work into English I discovered different areas of friction and resistance that it was important not to smooth over.

Echoing strangeness

Having outlined some of the background to translating Portante's work as well as my impetus for doing so, I will turn to my own translations and the process involved. The friction I have mentioned between Italian and French is one that resists easy assimilation into another language. Breathing usually happens unconsciously, without thought, and since there is no sounded word without breath, it is the beginning of every poem. In Portante's poetry, however, as for the whale, breathing prevents a completely fluid immersion in its environment; it remains a point of difference. As we began to discuss my draft translations, my most frequent question was: 'Does this sound as strange in French as it does in English?' The answer was almost inevitably affirmative, and the challenge was then not to domesticate but to allow the same Trojan horse dynamic to run through the English and make in it an echoing strangeness. Strangeness, in this collaborative context of translation, is a value that is mutually understood in terms of juxtaposition that prevents language from being transparent, but it also carries with it the suggestion of foreignness.

Following Lawrence Venuti's strictures against the invisibility of translation I have tried not to smooth the poems into an existing aesthetic in English, but to allow them to suggest a different one that would transform my own writing and my own language.[xvi] An example of this process is 'LA FIÈVRE DES CHOSES' from Portante's 2010 collection La réinvention de l'oubli:

Parmi les fatigues qui restent

laquelle garderais-tu

si l’arbre venait à disparaître:

si du tronc comme d’une ignorance de plus

ou de la brume tout autour se détachait

LA FIÈVRE DES CHOSES :

si chaque racine avait sa fatigue

et son tronc

qu’en garderais-tu :

et si à chaque racine était fixée une étiquette :

et si l’étiquette disait que ce qui disparaît

est ce qui reste quand tout autour

se détache des choses la fièvre

qu’en garderais-tu.

Among the remaining exhaustions

which one would you keep

if the tree came to disappear:

if breaking away from the trunk as if from

one more unknown or from surrounding mist was

THE FEVER OF THINGS:

if each root had its exhaustion

and its trunk

what would you keep:

if on each root was fixed a tag:

and if the tag said what is disappearing

and what remains when all around

the fever breaks away from things

what would you keep.[xvii]

The movement of translation here is inseparable from the process of definition that takes place in the source text. Relations between the tree trunks, the fever and the explanatory tags of language are unstable, but established in the terms of the poem through repetition, as so often in Portante's poems where a personal symbolism charges words with remade meaning. This is the mot voyageur in action, since by the end of the poem 'fever' and 'exhaustion' have taken on a meaning peculiar to this particular poem and its probing of memory and language. Rather than applying to a person, as might usually be expected, these symptoms are set in a landscape alongside things and the words for them ; they seem to behave independently in ways that would normally be impossible. The repetitive pattern establishes a tenuous but insistent logic that exists in sound, and in the memory of the poem, rather than any external reference point. This is the process whereby the poet writes not in French, Italian or English, but in an adaptation of Lacan, what Portante calls malangue, the language of the individual poet. He comments in an interview: 'Je pense que si un écrivain n’écrit pas dans sa propre langue, que d’ailleurs dans la psychanalyse on appelle une "malangue" – chacun a une "malangue" – si on n’écrit pas dans sa "malangue" alors on écrit dans la langue d’un autre et on n’est plus dans la littérature.'[xviii] We have considered the idea that, since we are both poets, my translations are not from French to English, but from the language of Jean Portante to the language of Zoë Skoulding. This may to some extent be the case, but a Portante poem does not sound like one of mine, and I am more interested in following the contours of a different voice than assimilating it to my own. That is, the translator, as much as the poet, may be in search of a plural identity.

Rhythm in discourse

In translating, the rhythm very often carries across into English because the poems are driven by speech patterns rather than metrical arrangement. There is a rhetorical structure in the build-up of conditional clauses, resolved with a question. Here, as so often in Portante's poems, there is a conversational feel, but it is also disrupted by the unexpected punctuation and capitalisation, and by forms of personification foregrounded by unusual choices of syntax. In the rhythmical subjectivity established in these poems, there is a tension between orality and writing that mirrors the tension between Italian and French. Since I do not speak Italian, it is by and large this friction between the oral and the written that alerts me to the poem's hidden Italian lung.

At this point it is helpful to turn to the poet and theorist Henri Meschonnic's observations on rhythm in poetry to clarify some of the issues at stake. He observes that rhythm in poetry is fundamentally unlike rhythm in music since it is never an abstract metrical pattern but always part of language as discourse.[xix] Meschonnic draws on Benveniste's observation that in pre-Platonic thinking on rhythm there is an opposition between rhuthmos (organisation of moving things) and skhêma (organisation of immobile things). Benveniste reveals a means of approaching rhythm not in its later sense of regular pattern but as 'la forme improvisée, momentanée, modifiable.'[xx] This consideration of rhythm as movement becomes, for Meschonnic, connected with a subjectivity that moves in and through language. The poem is the movement of the subject as language being unmade and remade anew ; rhythm is an individual movement, in contrast to the constraints of metre. In this view, language and life have the potential to be mutually transformative: 'Contre toutes les poétisations, je dis qu'il y a un poème seulement si une forme de vie transforme une forme de langage et si réciproquement une forme de langage transforme une forme de vie.'[xxi] This emphasis on poetry as a form of movement helps to clarify Portante's project, which explores the implications of writing understood as an individual and transformative linguistic trajectory. The ' Italian lung' of his work may be felt in lines like the following, with their rolling metrical pattern in which stressed syllables foreground the beginning of the line:

si du tronc comme d’une ignorance de plus

ou de la brume tout autour se détachait

LA FIÈVRE DES CHOSES :[xxii]

This is a form of resistance to French, where a more typical sonic structure would be a rapid movement towards an emphasis at the end. Rhythm, in Meschonnic's account, can be a means of describing that oscillation between languages that in Portante's case is a product of particular social and historical circumstances. He transforms the French language by breathing Italian through it, and in doing so, like every bilingual speaker, continues the long migration of all peoples and all languages, articulating a subjectivity that is simultaneously plural and minutely individual.

Listening to the 'voice' of the poem, therefore, involves paying attention to sound, but bearing in mind that the poem is already nomadic, it is important to catch its movement rather than impose on it a fixed point that must be replicated in translation. When I am translating I am not, for example, listening for 'the sound of sense' as Robert Frost puts it.[xxiii] For Frost, 'sense' is dependent on a shared context in which conversational cadence can carry meaning. In Portante's work the vitality comes from exactly the opposite: the space between languages, the break in sense as the cadences of Italian are heard through French. Within the source text there is already a conflict between sense as meaning and the sense-impression of sound; it is this conflict that creates a sense of direction and movement. For Meschonnic, the work of translation involves attending to the ear, and the range of syntactical and prosodic effects that shape meaning. His emphasis on the primacy of sound in translation might be seen as replacing fidelity to sense with an equally unattainable fidelity to sound, but he also comments on the spatial aspects of rhythm in ways that are useful in a reading of Portante, for example : 'Non, les mots ne sont pas faits pour désigner les choses. Ils sont là pour nous situer parmi les choses.'[xxiv] His emphasis on the materiality of sound reveals that words are also things. Rhythm is therefore a spatial movement, a process of situating, that may be answered if not reproduced in translation.

Breathing and transformation

There are repetitions in Portante's work in words and images carried from one book to the next; they build on previous articulations and resist dispersal. However, the sound of the poem is not based on metrical repetition, but an onward movement in which words and phrases are subject to continuous transformation. This can be seen in the following poem, which creates its own accretive context:

Dans l’œil de l’oiseau d’automne

avant qu’il ne parte

le jour paraît long :

long paraît aussi mais cela

nous ne le savons plus

le souffle qui tout autour

éteint et rallume les bougies :

nous creusons des métropolitains

dans leur cire

et aboutissons à des nuages

dont les contours perdent leur couleur

quand

TANT DE LUMIÈRE

y pénètre :

tout va vers l’absence

et à mesure que s’approche la clarté

le maintenant de ce qui reste

ressemble à l’oiseau d’automne

prêt à s’envoler :

nous le regardons

perché sur le vieux poteau noir

qui en a vu d’autres

et aimons nous dire

qu’entre celui qui en automne part

et l’autre qui au printemps reviendra s’y poser

il n’y a plus aucune ressemblance :

non que le voyage éteigne en eux

les longues bougies de l’oubli :

non que des longues bougies de l’oubli

comme d’un vieux poteau noir

dépende ce que l’automne a caché

dans l’œil de l’oiseau du printemps

avant qu’il ne parte.

In the eye of autumn’s bird

before it leavesthe day seems long

and it seems long too

though we no longer know this

the breath that all around

snuffs out and relights the candles:

we dig tunnels

in their wax

and end up at clouds

that lose their colours at the edges

when

SO MUCH LIGHT

gets in:

everything moves towards absence

and as clarity approaches

the now of what remains

looks like autumn's bird

ready to fly away:

we watch it

perched on the old black post

that has seen it all before

and like to say to ourselves

that between the one leaving in autumn

and the one that will come back to land there in spring

there's no longer any resemblance:

not that the journey snuffs out in them

the long candles of forgetting

not that on the long candles of forgetting

as if on an old black post

there hangs what autumn has hidden

in the eye of spring’s bird

before it leaves. [xxv]

There are moments of return but each repetition creates change ; in a rhythmical sense the migratory pattern is not a to and fro repetition but a continuous process of change, since what we come back to is full of hidden difference. The ambiguous qualities of breath are particularly in evidence in the sound of this poem, as it moves syntactically from one suspension to another. Breath is a central image, too, as it snuffs out and relights candles, which in the play between French and Italian, are also lies, a point explained in the earlier collection Le travail du poumon: 'en écrivant bougie, l'animal du dedans a glissé en elle l'italien bugia. Or, bugia signifie mensonge, et va donc, alors que la bougie sert l'éclairage, vers l'absence de lumière. Vers l’obscur.'[xxvi]

A pun like this cannot be translated, so it moves further into darkness with translation. The significance of the candle as an ambiguous illumination that is also a concealment is inevitably and ironically concealed by the translation. However, this may not be a bad thing. The tunnels dug in wax and the fading colours refer back to a moment in Fellini's Roma, a reference explained in the 'Mode d'Emploi ' of La réinvention de l'oubli : at one point in the film the process of building the metro system in Rome uncovers ancient frescoes, but at the moment when they are exposed they fade instantly. Most commentators on the film have attributed the fading to contact with air, but for Portante it is light, the rolling cameras that obliterate memory as they reveal it. When too much light gets in, the flickering of secret presence is lost. There is a parallel with the secret Italian lung, as Portante describes the sensation of reading his own work in Italian translation in the following terms: 'In seeing my poems, and also my prose returned to the maternal language by another's hand, it was as if this other was stealing the inside lung of my writing to expose it to the open air. Suddenly, the underground became the surface, and all the journey that linked the inside and the outside had disappeared.’[xxvii]

What might appear to be complete translation is in fact, therefore, a betrayal of the poem's dynamic between concealment and revelation. This particular kind of disappearance does not arise with translation into English ; the pun may not be translatable but the 'long candles of forgetting' are sufficiently out of line with colloquial English expression to signal the presence of imagery that cannot be made fully transparent.

If my translations of these poems do not arrive in English with a sense of complete resolution, this is because I read in Portante's work a poetics that depends on a continuing movement through multiple personal histories as well as the collaboration of translation. The rhythmical sounding of the poem places it between languages, between speakers and between breathing beings; like breathing, the poem is a negotiation between hidden interiors and the open air of shared discourse. To return to Joris and his nomadic poetics, English translation adds one more element to a body of work that is already linguistically multiple, one more journey to a poetry that is already on the move.

[i] Jean Portante, Les mots voyageurs [rubrique régulière] Le Jeudi. - n°1 ff. (2009 – 2019).

[ii] Jean Portante, In Reality: Selected Poems, trans. from French by Zoë Skoulding, Bridgend. Seren, 2013.

[iii] Jerome Rothenberg, Pologne 1931, trans. from English by Jean Portante and Zoë Skoulding, Paris, éd. Caractères, 2013.

[iv] Zoë Skoulding, Teint: For the Bièvre / Teint Pour la Bièvre, trans. from English by Jean Portante, Hafan Books, 2016.

[v] Pierre Joris, A Nomad Poetics: Essays, Connecticut, Wesleyan University Press, 2003, pp. 43-44.

[vi] Arthur Rimbaud, Arthur Rimbaud, Lettre à Paul Demeny, 15 mai 1871 in Rimbaud: Complete Works, Selected Letters, a Bilingual Edition. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2010, p. 372.

[vii] Sean Bonney, Letters Against the Firmament, London, Enitharmon, 2015, p. 140.

[viii] Pierre Joris and Jean Portante, « Whales, Ghosts and Nomads: A Dialogue », Poetry Wales 46.3. 2011, p. 10.

[ix]Joris and Portante, 2011, p. 11.

[x]Joris and Portante, 2011, p. 11.

[xi] Jacques Derrida, Le monolingualisme de l'autre. p. 13.

[xii] Derrida, pp. 21-22.

[xiii] Derrida, p. 44.

[xiv] Joris and Portante, p. 11.

[xv] Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths and Helen Tiffin, The Empire Writes Back: Theory and Practice in Post-colonial Literatures. London, Psychology Press, 2002, pp. 37-38.

[xvi] Lawrence Venuti, The Translator's Invisibility. London, Routledge, 1995.

[xvii] Jean Portante, trans Zoë Skoulding, In Reality: Selected Poems. Bridgend, Seren, 2013, pp. 52-53.

[xviii] https://poesiemuziketc.wordpress.com/2013/04/24/poete-interview-avec-jean-portante-sur-le-metier-du-poete/ Accessed 03.06.18.

[xix] Henri Meschonnic Critique du rythme p.121.

[xx] E. Benveniste, « La notion de “rythme” dans son expression linguistique » (1951), Problèmes de linguistique générale. Paris, Gallimard, 1966.

[xxi] Henri Meschonnic, « Manifeste pour un parti du rythme », http://www.berlol.net/mescho2.htm,1999. Accessed 03.06.18.

[xxii] IR p. 52.

[xxiii] In a letter of 1913, Frost comments: « The best place to get the abstract sound of sense is from voices behind a door that cuts off the words… it is the abstract vitality of our speech. » In his view, even if the words behind the door are indecipherable, cadence can be understood. However, this depends on an underlying familiarity with a shared context. Frost, R. (1913). Letter to John T. Bartlett, July 4, 1913. In Selected Letters of Robert Frost, ed. L. Thompson. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964, pp. 79-81.

[xxiv] Meschonnic, « Manifeste pour un parti du rythme ».

[xxv] IR pp. 64-65.

[xxvi] Jean Portante, Le travail du poumon. Paris, Le Castor Astral, 2007.

[xxvii] Joris and Portante, p. 14.

Zoë Skoulding is a poet and literary critic interested in translation, sound and ecology. She is Professor of Poetry and Creative Writing at Bangor University. She received the Cholmondeley Award from the Society of Authors in 2018 for her body of work in poetry. She was Editor of the international quarterly Poetry Wales 2008-2014 and co-founded the (North) Wales International Poetry Festival in 2012.