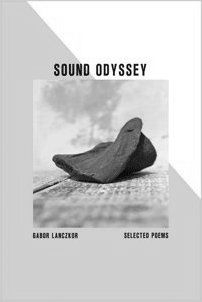

Sound Odyssey, Selected Poems, by Gabor Lanczkor, Paperwall, 2016

Reviewed by Pramila Venkateswaran

Hungarian poet, Gabor Lanczkor, presents us in Sound Odyssey, selected poems from some of his previously published poetry books, translated into English. Reading this selection, we are introduced to Gabor’s ruminative, dark, and existentialist style, reminiscent of Samuel Beckett and Bertolt Brecht.

Gabor does not shy away from exploring the nature of pain, of humanity’s embrace of darkness. In his poem, “Dream Border,” in the first section, “Table,” he imagines a needle pierced into his pupil “like a kid pins a murdered / hard-winged bug into his insectarium.” Evil is something many countries have first-hand knowledge of in the 20th and 21st centuries; Gabor’s images shock us with their starkness: “snapped umbilical cord,” “tulips on the wane”, “visibility like oblivion.” Personal pain spills into the environment, just as authoritarianism wrecks personal longing.

In the selected poems from Goya’s Deaf House, Gabor recounts an encyclopedia-like entry of Goya’s painting, then takes us on an absurdist journey into the experience of Goya’s art work. Here the style is more fractured, depending on juxtaposition and irony. Different dimensions of reality jolt us awake to a fractured reality brought alive through fractured syntax.

The poems in the middle section, “Sound Odyssey,” are written in a series of active voice statements and has the feeling of measured breathing. The play with sound patterns keeps us interested in their movement; for example the harsh “r” sounds contrasting with the “sh” and “s” sounds” in “A Partner.”

While the poems in most of Gabor’s book are spare, with their Imagist style, the poems in “Coins for Amrita” are written in a flowing prose style. These poems, the best in this selection, move us with their haunting narrative of the painter Amrita Sher-Gil’s life, her hybridity, Hungarian and Indian, both in her paintings and in her personal life. The straddling of identities is both fascinating and devastating at the same time, and Gabor lets us experience Amrita’s angst. The lyricism of the last few poems is haunting. The final lines of “Amrita Died,” “I truly believe,/ that it is only me that can embrace / my colours, /only me, / only, only me” continue to resound in our ears long after we close the book.

Gabor does not shy away from exploring the nature of pain, of humanity’s embrace of darkness. In his poem, “Dream Border,” in the first section, “Table,” he imagines a needle pierced into his pupil “like a kid pins a murdered / hard-winged bug into his insectarium.” Evil is something many countries have first-hand knowledge of in the 20th and 21st centuries; Gabor’s images shock us with their starkness: “snapped umbilical cord,” “tulips on the wane”, “visibility like oblivion.” Personal pain spills into the environment, just as authoritarianism wrecks personal longing.

In the selected poems from Goya’s Deaf House, Gabor recounts an encyclopedia-like entry of Goya’s painting, then takes us on an absurdist journey into the experience of Goya’s art work. Here the style is more fractured, depending on juxtaposition and irony. Different dimensions of reality jolt us awake to a fractured reality brought alive through fractured syntax.

The poems in the middle section, “Sound Odyssey,” are written in a series of active voice statements and has the feeling of measured breathing. The play with sound patterns keeps us interested in their movement; for example the harsh “r” sounds contrasting with the “sh” and “s” sounds” in “A Partner.”

While the poems in most of Gabor’s book are spare, with their Imagist style, the poems in “Coins for Amrita” are written in a flowing prose style. These poems, the best in this selection, move us with their haunting narrative of the painter Amrita Sher-Gil’s life, her hybridity, Hungarian and Indian, both in her paintings and in her personal life. The straddling of identities is both fascinating and devastating at the same time, and Gabor lets us experience Amrita’s angst. The lyricism of the last few poems is haunting. The final lines of “Amrita Died,” “I truly believe,/ that it is only me that can embrace / my colours, /only me, / only, only me” continue to resound in our ears long after we close the book.